Do Timeouts Stop Opponent Runs?

A Causal Impact Analysis

We’ve seen it a million times:

Team 1: made jumper +2

Team 2: shot clock violation

Team 1: made fast break layup +2

Team 2: lost ball

Team 1: made three +3

Team 2: timeout

Sure, it seems obvious - call the timeout, stop the crowd noise, and reset the momentum. But does this timeout really stop the momentum? Does it do anything?

In my first post, I examined the effectiveness of calling a timeout at the end of a quarter to run a play instead of taking a heave or running the full court with a short running clock.

I found that, in these scenarios, teams can gain an expected 0.2 points from calling a timeout instead. However, the million dollar question is: does that make it a good use of a timeout?

NBA teams get 7 timeouts per game, and some of them are used as mandatory timeouts.

Coaches have a variety of reasons for calling timeouts: making a lineup change, an in-game strategic adjustment, getting their players some rest, or, likely the most common, to stop an opponent run.

With so many reasons to take a timeout, and not even being in full control of all of them, coaches are faced with tough decisions about when to use their timeouts.

In this blog post, I’ll evaluate the effectiveness of the most common timeout: stopping an opponent run.

Methodology

Using play-by-play data, I created a dataset of 1.6 million possessions since the timeout rules changed in the 2017 offseason.

I then aggregated this data into 115k stints, which are sessions of play, only interrupted by timeouts and the end of quarters. I’ll use these stints to understand the flow of momentum and whether the presence of a timeout causes a meaningful change.

Some notes about what is and is not included:

I excluded the last 6 minutes of the fourth quarter and overtime

I removed all stints that contained a coach’s challenge, as this isn’t a momentum-stopping timeout

I removed all stints whose future 10 possessions spanned multiple quarters

I’ll aim to show the causal effect of taking a timeout as it relates to stopping an opponent run using five different methods, starting with the most basic and ending with the most advanced.

Method #1: Timeout vs. No Timeout

The simplest way to measure a timeout’s impact is, for each possession, note whether a timeout was taken, then track the following possessions and compare average outcomes.

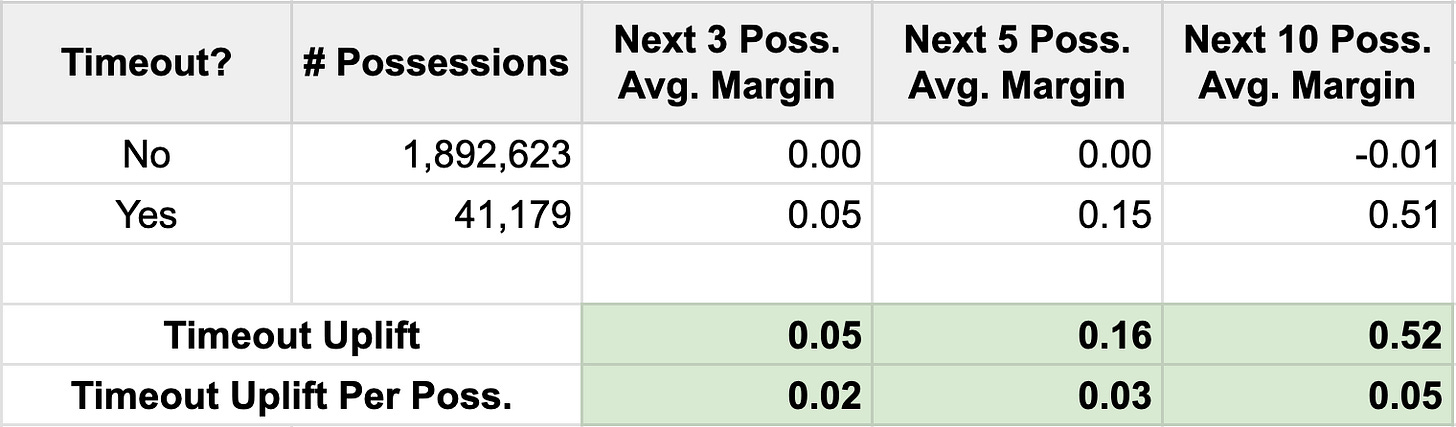

Using this method, I found that calling a timeout is worth about .05 points over 3 possessions, 0.16 points over 5 possessions, and 0.52 points over 10 possessions:

How to read above table:

Think of a single possession as possession #0. Was a timeout taken on this possession?

For both timeout possibilities, calculating the team’s average margin over ensuing possessions #1-3, #1-5, and #1-10

When a timeout was not taken on possession #0, a team’s average margin over the next 3 possessions was 0.00 points.

When a timeout was taken on possession #0, a team’s average margin over the next 3 possessions was 0.05 points.

On a per possession basis, this timeout is worth 0.02 points.

My takeaway: this is something in support of timeouts improving future performance, but the methodology leaves a lot to be desired.

We don’t know anything about the context as to why these timeouts were or were not taken. We’re not even looking at whether a team had allowed an opponent run, let alone stopped it. That will bring us to method #2.

Method #2: Timeout vs. No Timeout (7-12 point opponent run)

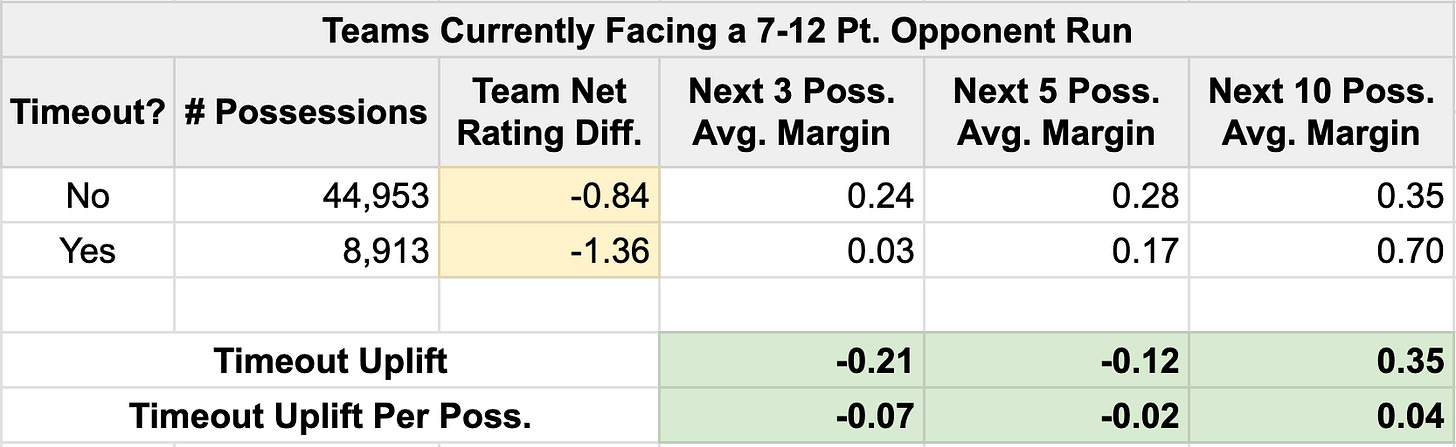

Now I will re-run the same analysis for teams who are, during one stint, getting outscored by their opponents by 7-12 points.

Here, it looks like the effectiveness of a timeout is worse:

I have two initial observations from this table:

Regardless of a timeout called or not, the future margins for a team down 7-12 points on a stint are all positive.

This shows evidence of regression to the mean and/or the rubberband effect. Opponent runs don’t last forever - most of the time, teams will eventually bounce back with or without a timeout.

Where we used to see a timeout generating a positive uplift in the next 3-5 possessions, we now see timeouts showing a negative effect.

How could this be? Surely teams wouldn’t get worse after calling a timeout?

In terms of causal analysis, there’s evidence of a confounding variable. Pay attention to the new column in yellow called “Team Net Rating Difference.”

I added the net rating of each team for the last 50 games entering each game. Note that, for teams who did call a timeout for a given possession down 7-12 points in a stint, their average net rating vs. their opponent is worse than teams who don’t call a timeout. So what does this have to do with anything?

Take an extreme example like the ‘24-’25 Cavaliers vs. the ‘24-’25 Wizards. If the Wizards go on a quick run, the Cavaliers are less likely to panic, knowing that over the long run, they’ll bounce back on their own.

This exact situation happened on February 7, 2025 between the Cavs and Wizards. These teams had a staggering net rating differential of 25.9 over the previous 50 games (CLE: +10.8, WAS: -15.0), and Cleveland found themselves down 15-7 to start the game.

However, they did not call timeout - it was Washington that called timeout a couple minutes later, and less than 90 seconds later, the Cavs found themselves up 19-17.

In my next two methods, I’ll create better like-for-like scenarios of team matchups and timeout likelihoods that will better isolate the impact of a timeout.

Method #3: Propensity Modeling (Logistic & Linear Regression)

Causal impact is all about creating similar test and control environments.

In this case, in the control scenario, a team is X% likely to call a timeout but doesn’t.

In the test scenario, a team is X% likely to call a timeout and does.

When we create equal situations (as best as possible), we can isolate the impact of a timeout and attribute the change in future performance to the timeout itself.

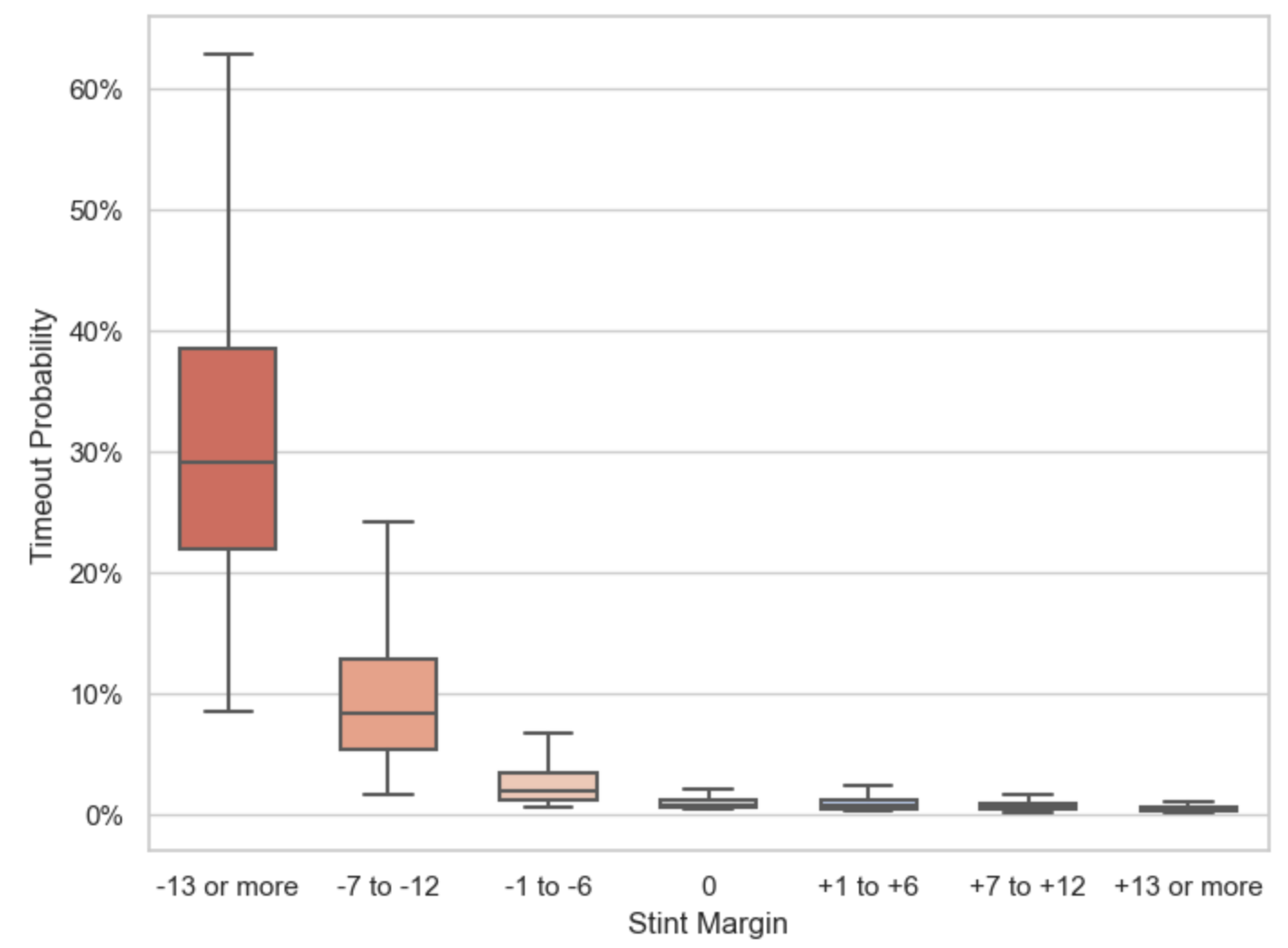

In order to determine whether a team is likely to call a timeout, I created a simple propensity model. Using logistic regression, I assigned a likelihood of a team to call a timeout from 0% to 100% for each possession. The only variables included in this propensity model are (1) current stint margin, (2) length of stint in possessions, and (3) team net rating differential.

The results are found below:

As expected, teams’ likelihood to call a timeout is directly proportional to their current stint performance. Teams outperformed by 13 or more have a median likelihood of calling a timeout of almost 30%, roughly three times higher than the next group of -7 to -12.

We can now take into account the timeout probability into determining the effectiveness of a timeout. The reason this is important is that it allows us to essentially match situations where teams had equal timeout likelihoods, but some took a timeout and some did not.

To do this, I ran a simple linear regression using the following inputs:

Net rating differential

Timeout probability

Timeout

Home court advantage

Against the following outputs:

Next 3 possession average margin

Next 5 possession average margin

Next 10 possession average margin

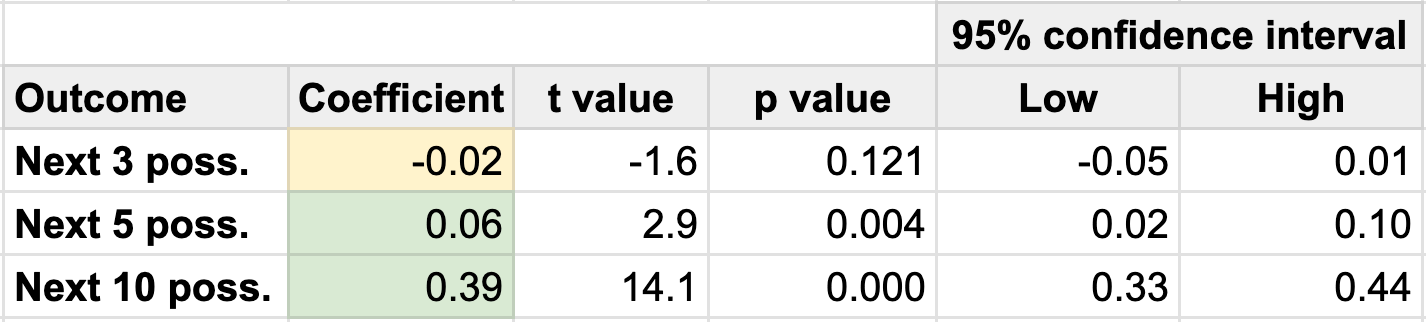

The results are found below:

My initial observations are:

Given the p-value is above 0.05, a timeout did not have a significant effect on improving the next 3 possessions.

A timeout showed a small but significant effect on the margin of the next 5 and 10 possessions.

On a per-possession basis, the timeout is worth about 0.01 points for the next 5 possessions and 0.04 points for the next 10 possessions.

So far, we have evidence that a timeout might produce a very small uplift in future performance, but there are a couple more approaches I’d like to attempt.

Method #4: Doubly Robust Weighting

As I mentioned above, the goal of causal impact is to create a cause and effect. When we don’t have a counterfactual, or a “what would have happened,” we have to create the circumstances for it ourselves.

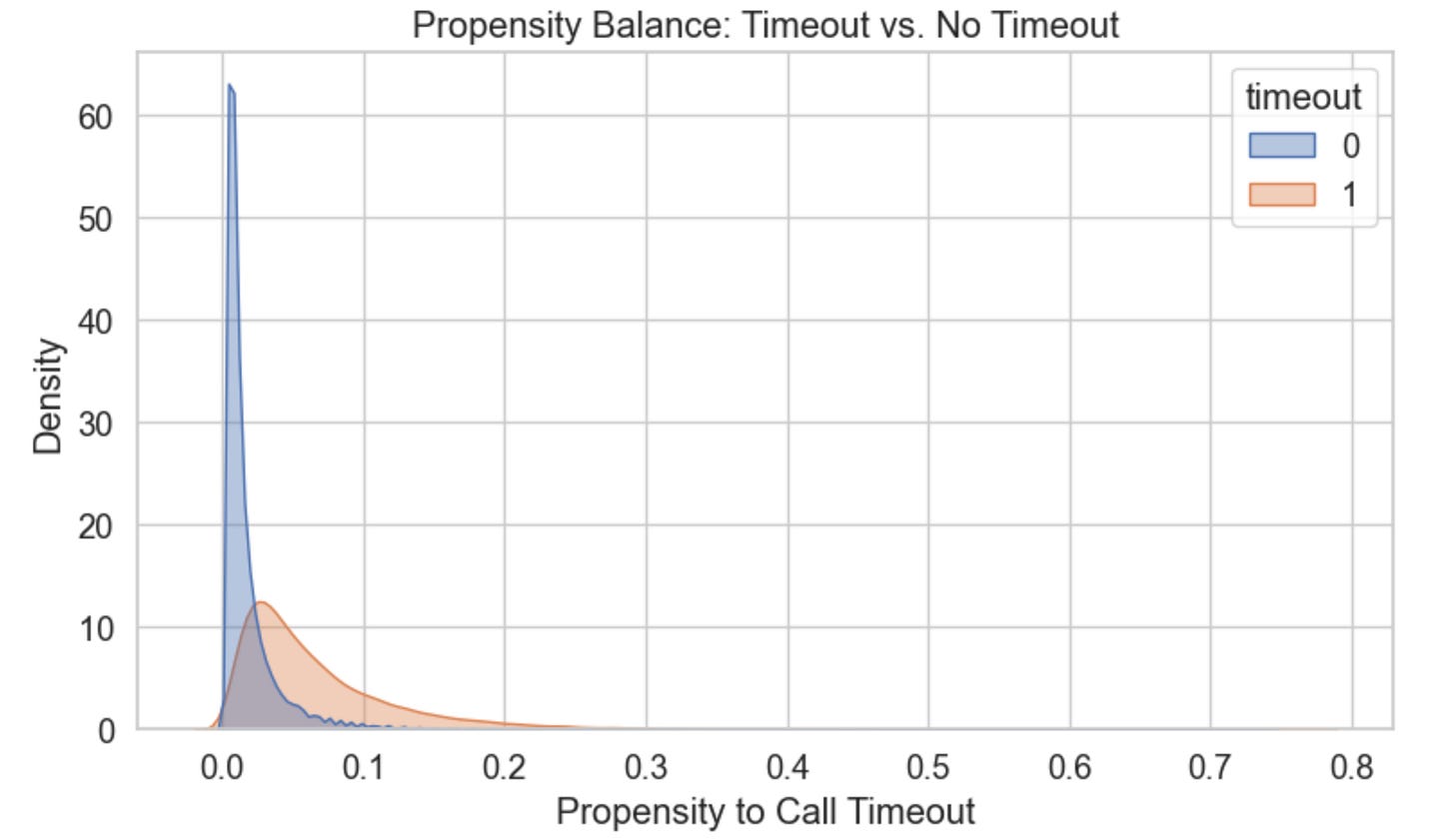

While the last step’s regression attempts to account for the probability of a timeout, we’re still left with the reality that there’s an imbalance in timeout probability distribution between timeout = 1 and timeout = 0:

This causes an issue in our causal impact analysis, as we’re still not exactly comparing like-for-like situations.

A doubly robust model uses Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) to weight the data based on timeout propensity. The weighting balances the distribution of timeout probability, the confounding variable between groups, which helps to create a simulated randomized experiment.

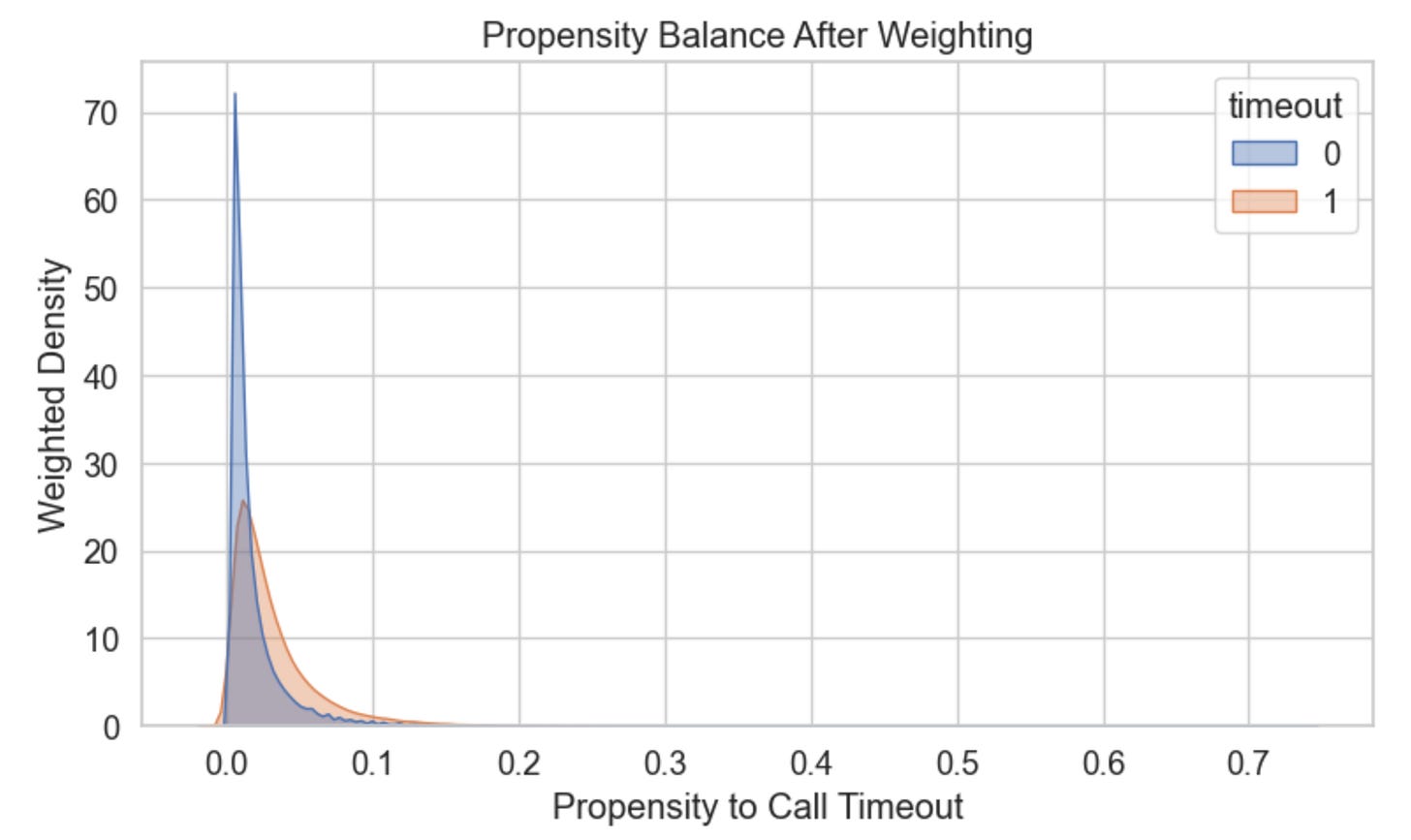

After reweighting, our propensities between groups look more similar:

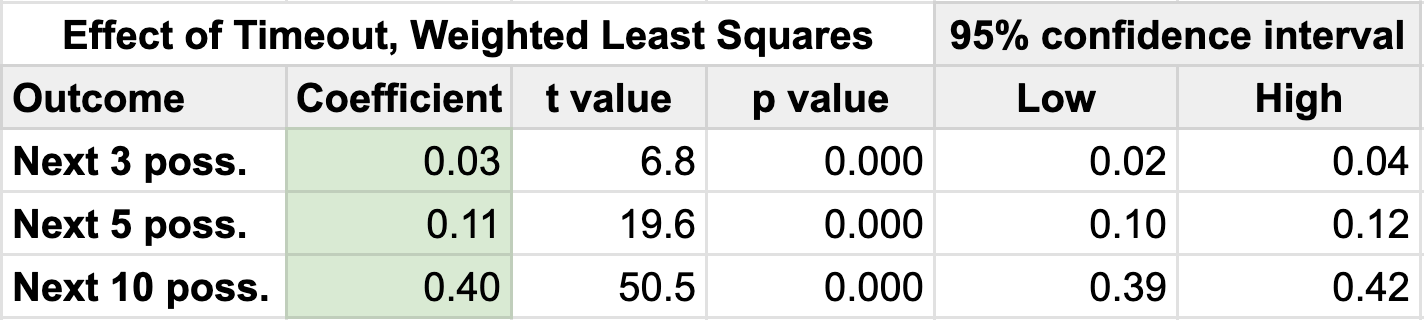

Using these weights, I can now replicate the linear regression from the previous step and instead use a weighted least squares regression:

In this case, we see that the presence of a timeout does show a small but significant uplift in performance over the next 3, 5, and 10 possessions. On a per possession basis, these numbers are even smaller (0.01, 0.02, 0.04 points per possession).

This is the most compelling evidence we have that timeouts do something, but I want to focus in on situations when an opponent has generated a run.

Method #5: Doubly Robust Weighting (Opponent Outscores by 7+)

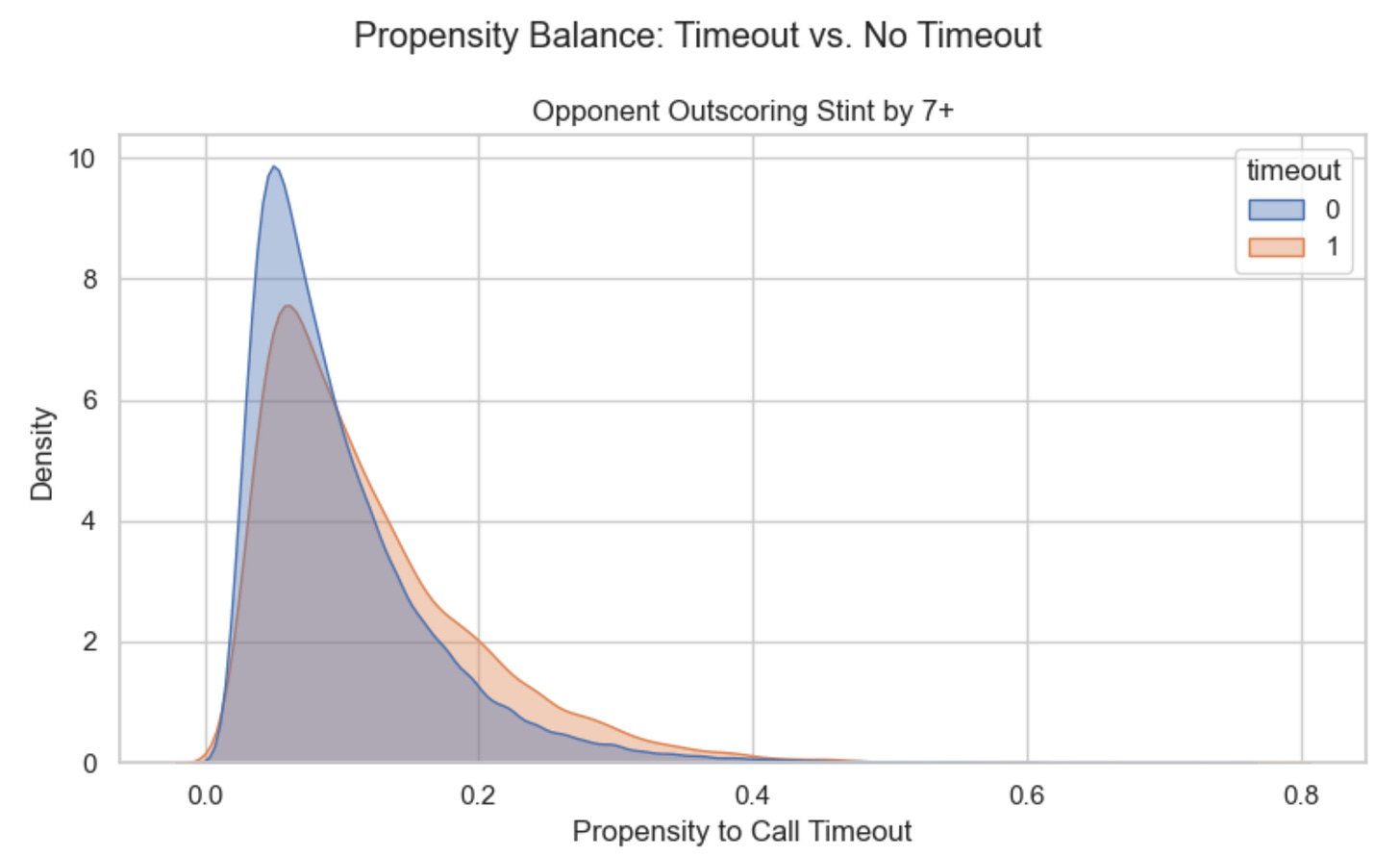

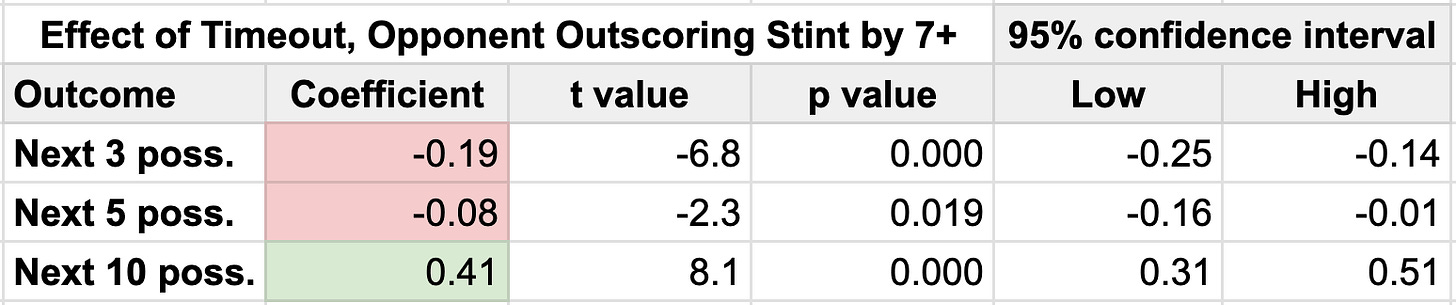

I replicated this method for only situations when a team is down by 7 points or more in a stint.

Given we have filtered down to a very specific game situation (<3% of all possessions), the timeout propensities between groups look much more similar:

When re-running the doubly robust weighting approach, we see some very interesting results:

The presence of a timeout shows a significant negative effect on future performance for the next 3 & 5 possessions, and a significant positive effect for the next 10 possessions.

This is difficult to explain, but I’ll share my hypotheses:

Though statistically significant, the coefficients are still very close to 0, which suggests timeouts in these situations have a very small impact one way or another.

Despite the improvements in methodology, I believe we’re dealing with a case of omitted variable bias.

It’s difficult to predict performance of NBA events in general, but it’s especially difficult with only 4 input variables.

There are perhaps dozens of inputs that would be very helpful in predicting future team margins that are currently not included, such as players on court, coaching effects, rest, lineup combination effects, and more.

With this few number of inputs, it’s easy for one input to appear statistically significant.

Given how close the coefficients are to 0, it could very possibly be due to chance that some are positive and others negative.

My takeaway: for stopping an opponent run of 7+, there isn’t a lot of evidence that timeouts have a strong effect on performance one way or another.

Closing Thoughts

There isn’t strong evidence to show that timeouts generate a strong uplift in performance in general. The evidence in favor of stopping a run is even weaker.

This isn’t to say that timeouts are worthless - if the coaching staff sees an opportunity to make an adjustment either through a lineup or scheme change, this is likely still a good use of a timeout.

My opinion is that teams should not call a timeout for momentum’s sake only.

I think it’s time for teams to get more creative with their use of timeouts - they should consider strategies like a full court play at the end of a quarter, as this shows a higher performance uplift.

Teams should attempt to let their opponents call a timeout for rest purposes. You might be thinking: what if the team is completely gassed and needs a break? Fair, but this is one of the benefits of having a well conditioned team. If you can outlast your opponent, you can save your timeouts for the most critical moments.

This is straight 🔥. I would imagine that in high school basketball this would change significantly?

WOuld love to see this kind of report in the college game. Just between worse/inexperienced players, a different style of game, where timeouts fall in halves, etc…